Today I went on an exploration of Kensal Green cemetery, with geologist Diana Clements.

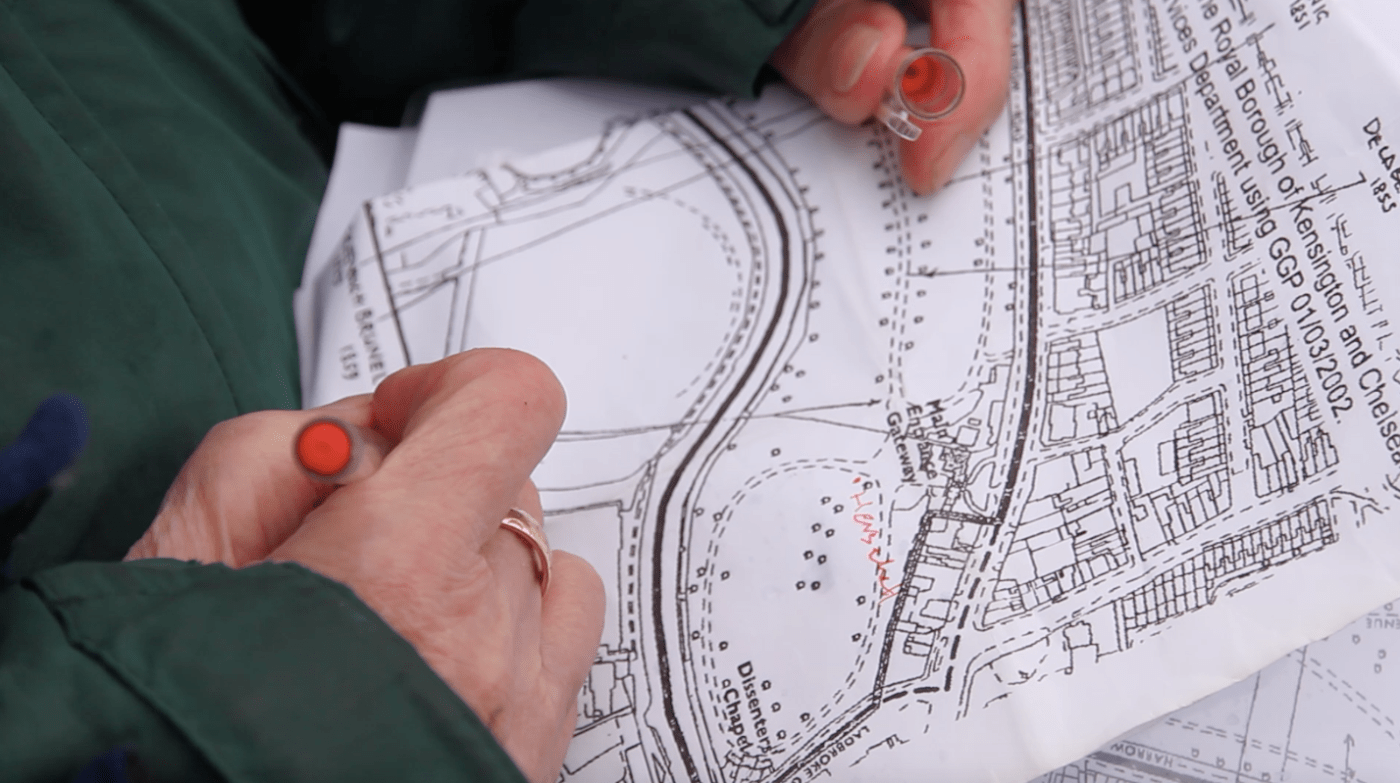

We were looking for famous geologists, engineers and zoologists, marked on the map drawn up by former local resident geologist, Eric Robinson, who led many groups around the cemetery looking at the graves and the stones they were made from

At the same time we were paying attention to the various stones the graves are made from, whether granite, marble, sandstone, limestone, slate and others.

Diana explained to me how some of the rocks were formed, but also how, depending on their compositions, are effected by weather conditions. The limestone is susceptible to weathering, especially the acid rain which would have come from the nearby gas works, while granite is more robust.

Diana pointed out to me various types of stones and their origins, which are often from quite faraway. Stone was brought over to London by sea, canals, and later by railways. There is a lot of Portland stone at in the cemetery brought over by sea from Portland. Portland stone is the favoured building stone of London as it was easy to load onto ships directly from the quarries around the island. Wren was the first to bring it in any quantity for rebuilding the City churches after the fire of 1666.

Textures of stone became more vivid in the rain, here quite iridescent.

Red sandstone, probably coming from the Midlands (like the St Pancras Hotel in St Pancras Station, which would have come from Midlands by rail).

The stone peals off, due to exposure to water and frost. Here the sandstone is covered by lichen. Different types of lichen grow on particular types of rocks.

John Smeaton (1724-1792), civil engineer

Close up textures, with traces of moss and lichen

Note: Granite is formed within the crust of the Earth when Felsic magma, that is magma that is rich in Silica, cools down without reaching the surface. Because it remains beneath the surface as it is cooling it forms large crystals (ie, you can see the individual crystals without need of a microscope or hand-lens). It has a minimum of 20% Quartz with up to 65% of the rock being Feldspar. Other minerals such as Mica are usually present and can make up to 25% of the total volume..

Diana next to George Bellas Greenough’s grave.

George Bellas Greenough (1778 – 1855) pioneering English geologist, founding member of Geological Society, London

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806 – 1859) English mechanical and civil engineer who is considered “one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history”.

stone chipping (green slate) surrounding Brunel’s tombstone

Fallen angel

James Combe (1806 – 1867) a civil engineer, his grave is made of polished granite

Thomas Russell Crampton (1816 – 1888), British engineer

Peterhead granite above. We also saw a darker red granite called Balmoral, which, as Diana explained, is actually from Sweden

Hugh Falconer (1808 – 1856) Falconer was a Scottish palaeontologist, geologist and botanist

George Busk (1807 – 1886), British naval surgeon, zoologist and palaeontologist

James Meadows Rendel (1799 – 1856), civil engineer

Special moss font spotted on one of the graves

Charles Babbage (1791 – 1871), English mathematician, philosopher, mechanical engineer and (proto-) computer scientist who originated the idea of a programmable computer.

Diana taking notes

About Diana Clements (London Geodiversity Partnership)

Diana became interested in the geology of London when researching her own area, Islington, and she went on to mount an exhibition in the Islington Museum. More recently she compiled a Guide to the Geology of London for the Geologiststs’ Association and now works with the London Geodiversity Partnership to identify, conserve and interpret London’s geology.

Upcoming workshop with Diana Clements will take place on 18th March, at the Dissenters Chapel. Please get in touch if you’d like to participate. Below more detail:

Beneath your feet: a geology workshop based on Kensal Green and the wider London area

Have you ever wondered what lies beneath your feet? In an urban area it is not something we think of very often. A cemetery is a good place to start looking as grave diggers allow us a glimpse. For the workshop the geology beneath Kensal Green and the wider London area will be explained and examples of the rocks and fossils found will be passed round for discussion. We will consider the environments relating to the various rock-types going back over the past 100 million years and can look into the future of where Britain may be 100 million years hence.

Wow, this is such a great project! I wish I could take part. I was researching the Brno cemeteries before and the interest never goes away….Karin